- guardian.co.uk,

- Friday May 30 2008

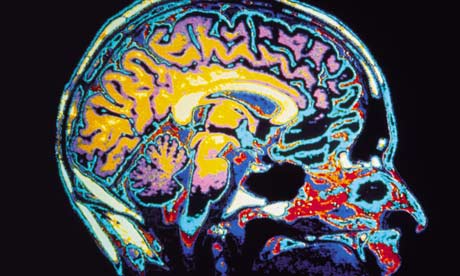

Photograph: Howard Sochurek/Corbis

Scientists have developed a method for reading a person's mind using brain scans.

Once it has been trained on an individual subject's thoughts, the computer model can analyse new brain scan images and work out which noun a person is thinking about - even with words that the model has never encountered before.

The model is based on the way nouns are associated in the brain with verbs such as see, hear, listen and taste. The research will inevitably raise fears that scientists could soon be able to read a person's mind without them realising.

The researchers have dismissed this idea pointing out that their model needs to be trained on each new individual before it will work. Also, the scanning requires the subject to lie very still in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner - massive bulky machines that use extremely powerful magnets.

Fooling a would-be Big Brother scientist would be easy, said team member Dr Tom Mitchell of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. "All you need to do to give us trouble is to jiggle your head, or just think about lunch instead of the word on the screen," he said.

More importantly, the research is a great advance in scientists' understand of how words are coded in the brain.

"The paper establishes for the first time that one can predict the pattern of neural activity associated with thinking about many different nouns, from the verbs that co-occur with that noun," said Mitchell. "It can't yet decode arbitrary thoughts, but it does well on a multiple-choice test with two choices."

The team scanned the brains of 9 volunteers using functional MRI as they

viewed 58 nouns such as body parts, vehicles and vegetables. The scanning

technique detects increases in blood flow in the brain when different regions

are activated.

The team then categorised the nouns using an electronic

database of texts that contained more than a trillion words. They were looking

for how often each of the nouns appeared together with simple verbs such as

push, run, fear and open.

Next they matched this pattern of co-occurrence with the brain scan patterns and found that the brain does something similar. "The meaning of an apple, for instance, is represented in brain areas responsible for tasting, for smelling, for chewing. An apple is what you do with it," said Prof Marcel Just, who led the study.

To test the model, the researchers showed the volunteers two new nouns which were also subjected to the same textual analysis. The model then predicted what it expected the brain scans for those nouns to look like.

By comparing these with the real scans it guessed which of the nouns the person was really looking at. The model was correct 77% of the time, significantly better than chance.

"Philosophers, psychologists, linguists and others have debated for centuries

how the brain organises and represents meaning. But they were hampered in

debating these issues because they lacked experimental data," said

Mitchell.

"[We have] established for the first time a direct connection

between how a word is used in a large collection of typical language, and the

neural activity the brain uses to represent the word's meaning."